By Matt Ventresca

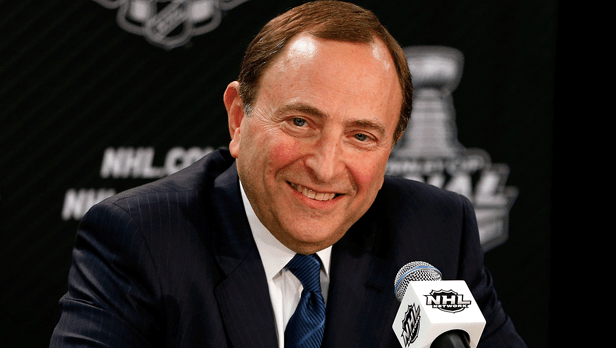

Last Friday, NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman was deposed in a private hearing in New York as part of the substantive legal action regarding the league’s mishandling of head injuries. The lawsuit is on behalf of at least 60 former players who sustained concussions during their pro hockey careers. This list includes some names that might ring a bell to casual hockey fans, such as Bernie Nicholls, Gary Leeman, Dave Christian and Mike Peluso. This group contends that the NHL didn’t do enough to communicate the risks of concussions to its players and protect them from the effects of head injuries throughout or following their playing days. The litigation comes on the heels of a multi-million dollar settlement awarded to over five thousand retired National Football League (NFL) players who brought forth a similar lawsuit a few years back.

Some sportswriters, including Allan Muir of Sports Illustrated, have suggested that Bettman’s deposition should be made public (a decision that rests in the hands of Judge Susan Nelson, who is presiding over the case). Muir argues that Bettman’s unfiltered comments on the concussion issue might constitute the most significant hockey story of the year, and, yet, the public may never know the contents of this meeting.

Muir is also right to point out, however, that Bettman’s testimony, even if it ever sees the light of day, will likely not provide the “smoking gun” the players and public might be looking for. Muir writes that Bettman, an experienced, Ivy League-trained legal mind, was probably not intimidated by the deposition environment and likely did not stray from the carefully-crafted legalese that has served as the NHL’s company line on the concussion issue.

In the face of mounting scientific evidence outlining the links of repetitive head trauma to serious long-term physical and mental health challenges, Bettman and the NHL’s executive have remained resolute in downplaying the connections between pro hockey, concussions and degenerative brain disease. Despite the all-too-frequent moments of tragedy associated with the league – including the deaths of Derek Boogaard, Wade Belak, Rick Rypien and, most recently, Steve Montador – and the heartfelt pleas from current players to address the concussion problem, Bettman has issued fierce denials regarding the league’s culpability in the growing number of current and former players experiencing the damaging effects of concussions.

When Bettman met with the media in Chicago during this year’s Stanley Cup playoffs (mere weeks after Montador’s death), he repeated the NHL’s longstanding defense against cries that the league come clean regarding the link between hockey and brain injury. He declared, “From a medical science perspective, there is no evidence yet that one necessarily leads to the other.” The commissioner continued, “I know there are a lot of theories, but if you ask people who study it, they will tell you there is no statistical correlation that can definitely make that connection.” Bettman’s language here is telling: there is no “evidence yet that one necessarily leads to the other” and “no statistical correlation that can definitively make that connection.” The NHL’s position is made clear through Bettman’s comments. The league must wait for indisputable scientific proof that hockey causes brain damage before it can make an informed decision about how it should best address the concussion problem.

Funeral for Steve Montador (Mississauga.com)

Yet the subtext beneath this piece of public relations wizardry is just as important to decipher as what Bettman actually says. Bettman is also appealing to the moral justification behind the NHL’s inaction on the concussion issue. Put simply, if we currently don’t know enough to establish definitive proof of hockey’s connection to concussions, then the league can be excused from any responsibility (legal or otherwise) for the wellbeing of its players and the long-term health of their brains. The league can’t be accused of inadequately communicating the risks of concussions to its players when there is still so much we don’t know about the effects of professional hockey on the brain.

In some respects, Bettman is right (and it absolutely pains me to write that). Although important advances have been made in neuroscientific and sports science research about head injuries, there is still a great deal we don’t know about the relationship between concussions and a contact sport like hockey. I would add that there is also a major need for more studies examining the psychological and social contexts in which concussions are sustained, diagnosed and treated. Yet my research into the sociological aspects of the concussion problem shows that pro sports leaders like Bettman (and others like NFL commissioner Roger Goodell) strategically point to these gaps in knowledge as a way to deflect criticism or defer responsibility for addressing the concussion problem.

Understanding this strategic state of “not knowing” is a key part of what is called the “sociology of ignorance.” Sociologists dating back to big thinkers like Georg Simmel (1858-1918) have grappled with questions about what it means to “not know.” Typically, lacking knowledge or awareness leads to a position of weakness or exclusion when trying to persuade the public. But scholars have also identified how claiming ignorance can sometimes be beneficial for those trying to make arguments in the public eye. Following this logic, Bettman (and others like Goodell) who state they are waiting for indisputable scientific proof of the cause-effect relationship between contact sports and concussions build their arguments around what we currently don’t know about the brain rather than what we do know: that growing numbers of hockey players are developing degenerative brain diseases during or after their pro careers and experiencing the often debilitating effects of these illnesses.

By arguing from a place of ignorance, Bettman uses the rhetoric of scientific reason and evidence to suggest that the increasingly massive body of research linking hockey to head injuries is not sufficient to necessitate substantial changes to the ways hockey is played, organized and marketed. Rather than accepting responsibility for the wellbeing of its players, the NHL, through its professed ignorance, places the burden of proof on the scientific community to find the indisputable evidence demonstrating beyond a shadow of a doubt that hockey causes concussions. Given the complex nature of the brain and the inability to definitively isolate incidents of head injury in a fast-moving sport like hockey, this type of silver bullet probably doesn’t exist. But by continually highlighting these gaps in knowledge, the NHL can resist making meaningful changes to the league’s rules and unwritten codes of masculine honour as it waits for “better science.”

While the NHL plays what could be a decades-long waiting game, they can continue to commodify violence as part of their marketing strategies. The sport’s culture can also remain tied to a value system where “playing tough” and “finishing your check” are not-so-subtle code words for an aggressive, violent style of play that puts athletes’ bodies (and brains) in danger (even as fighting and the enforcer role seem to be on the wane). The NHL should absolutely be pushed to fund more resources for players who have sustained head injuries throughout their careers (as Scott Wheeler of Pension Plan Puppets smartly argued last week). But how much investment in these types of programs will allow the league to continually evade questions about its promotion of hyper-masculine violence? How many solemn press conferences or moments of silence will be held before the NHL will be held accountable for how their brand gleefully promotes the violence that contributes to these injuries? How long can the league seek after-the-fact solutions to the concussion problem rather than advocating for progressive and proactive changes to the sport’s underlying culture? Understanding how Gary Bettman and the NHL’s power brokers strategically wield ignorance as a tool in these discussions is a crucial step in deconstructing the arguments that keep the answers to these types of questions behind closed doors.

Author’s Note: On last night’s finale of The Daily Show, Jon Stewart alluded to the influence of strategic ignorance in the realm of American politics. Using climate change denials as his primary example, Stewart described the “bullshit of infinite possibility” as follows: “These bullshitters cover their unwillingness to act under the guise of unending inquiry. We can’t do anything because we don’t know everything.” Thank you, Jon – I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Nice article. Thank you.

The sociology aspect is one that did not spring to mind immediately (despite the blog’s name!). Instead, noting that Bettman is a lawyer brought to mind the legal defense strategies of Big Tobacco. Decades of disease, suffering, and profits piled-up before those guys finally started to be held accountable. In the legal world, that’s a win!

Bettman is well versed in the Four Dog Defense:

1) My dog doesn’t bite

2) My Dog bites – it didn’t bite you!

3) My Dog bit you, it didn’t hurt you!

4) My Dog bit you – its not my fault.

He simply chooses which option to argue from. Time for this guy to go!

Pingback: Pens Points: NHL Still Ignorant on Concussions | Hockey Insider | NHL News, Drafts, Picks, Schedules & NHL Betting Online

Pingback: Kane is ‘a bad spot’; Canucks and racism; Ducks to debut new thirds (Puck … | Hockey Insider | NHL News, Drafts, Picks, Schedules & NHL Betting Online